How films like Fight Club, American Beauty, Office Space, & The Stepford Wives represent the malaise of white men facing a new era onscreen

By John Lutz

It’s hard to imagine a character like Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey) from American Beauty interacting with Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) from Fight Club, but odds are that the two would likely have a lot to talk about.

The key lies in the release of these two films: 1999. It was at this point that a wave of confusion washed over countless white males onscreen, forcing them to consider life, existence, and happiness. While white men struggled to come to terms with these quandaries, women rose high in the ranks, achieving long-deserved equal status. Technology, too, gained much ground, as offices adorned their walls and hallways with printers, fax machines and computers. This did little to quell men’s feelings, and in the case of some, became the very bane of their existence.

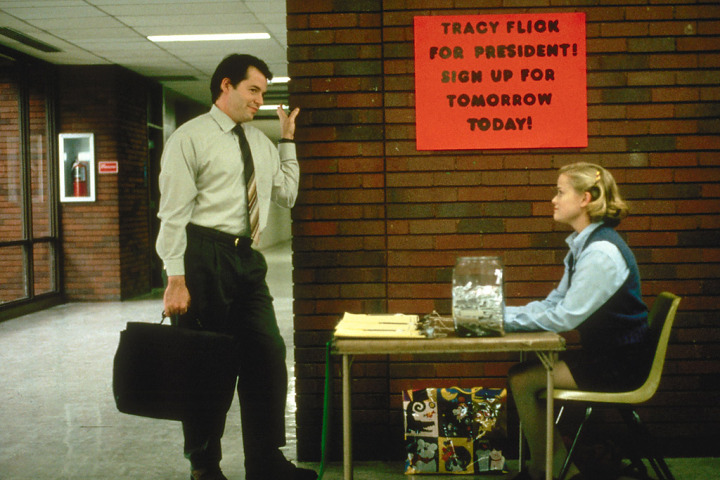

Perhaps one of the strongest examples of female empowerment writhing its way into the anger of many men lies in Alexander Payne’s film Election. Tracy Flick (Reese Witherspoon) proves to be the true thorn in the side of Jim McAllister (Matthew Broderick), a high school teacher and proctor of the school’s student election. As the film progresses, McAllister’s frustration evolves, progressing from mere annoyance to a skewed sexual frustration, eliciting many similarities to male characters in other films of the time. Lester from American Beauty immediately comes to mind, but even Edward Norton’s narrator in Fight Club becomes a mixture of frustration and arousal as Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) wriggles her way into male-dominated support groups. But all of this confused animosity had to arise from some new force, one that white men in particular would not have the clear upper hand in grasping.

Technology certainly contributed to this newfound attitude. As many researches have pointed out, the fear of technology, technophobia, relates to the concept of losing control. And this idea can be seen throughout history, with many noting its origins in America with the Industrial Revolution. Films have also played with this concept, and perhaps one of the strongest examples connecting technophobia to men exists in both the 1975 and 2004 versions of The Stepford Wives. Both versions find men connecting their phobias of technology and losing control over women. These films see men seeking to control and fully dominate their wives, making them mindless robots who complete every task requested, from inane cleaning to “passionate” fornication. Yet it’s Frank Oz’s 2004 version that really connects technophobia with the loss of control. The men of this film aim to connect the two, taking strong women with incredible, formerly male-dominated careers (e.g. Joanna’s (Nicole Kidman) power as a television executive), and seeking to make them characterless androids. Joanna’s husband, Walter (Matthew Broderick), notes of this feeling of loss and anguish in a speech to his wife about his lack of purpose or necessity in their marriage. The current study of a gender bias in AI devices (e.g. Alexa and Siri) provides further relevance to this idea, all the while cementing it as an undeniable development of the 21st century white male.

Yet, the idea of losing control over women has been a major theme of Hollywood for years, with director James Whale’s 1935 film Bride of Frankenstein standing as a shining example. The Bride only serves as a tool for both Doctor Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger) and Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive) to achieve what they want, all the while assuming Frankenstein’s Monster wants a woman. The only character who sees The Bride as a companion first and foremost rests with Frankenstein’s Monster. The collection of female parts to make The Bride correlate with the husbands from The Stepford Wives, as they cherry picked all of their best assets to create the ideal stay-at-home wife. It wasn’t about personality, character, or attitude; rather, it was about creating a model from the familiar, and as a result, stagnating technological development.

With Y2K encroaching in, terrified men felt a need to fight back and overcome the technology before it took over them. 1999 saw many films play with this concept, as white-collar office workers Peter (Ron Livingston), Samir (Ajay Naidu), and Michael Bolton (David Herman) go to town on Initech’s new copy machine to the tune of Geto Boys’ anthem, “Still,” in Mike Judge’s directorial feature, Office Space. Fight Club even features this “stick-it-to-tech” attitude, with Tyler Durden and his space monkeys of Project Mayhem aiming to destroy the credit card companies of the city by blowing them up with homemade explosives. These napalm goodies, as well as the whole concept of destroying companies holding credit card records, create Fight Club’s middle finger to consumerism, and ultimately the fate that was just around the corner. Just imagine The Narrator’s fascination with smart televisions and Alexa devices, only for Tyler to throw them out the window and evoke the wisdom of Nietzsche.

The bigger question to analyze today probably lies in discerning whether or not this kind of change-fearing male population still constitutes a wide array of the population. After all, many of the current industries, such as the tech industry, remain imbalanced with regards to gender. It goes without saying that both women and people of color have faced hardship and scorn from many white males throughout history. Jordan Peele challenges this concept in his 2017 directorial debut, Get Out. The ideas of loss of control and fear of power ripple throughout the film’s script, with elderly white folk seeking the keen eyes, strong builds, and creative spirits of many African American men. Peele clearly tips his hat to The Stepford Wives, yet calls upon racism and opposition to diversity instead of seeking female control. Get Out works so well and resonates with audiences so deeply for its connection to this current context. Aversion to African Americans and aversion to women both represent different fears, yet stem from the same hatred that’s permeated American culture. So while the Lester Burnham’s and Stepford Husbands of 20 years ago may be gone (in general), it seems that the fears that became realities for them have sent ripples into the white men of this current generation.