How Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Lobster provides a juxtaposed relationship-obsessed culture that is just as frightening as the real thing

By John Lutz

Users of apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge today don’t need to worry about turning into an animal at the sake of not finding a match. But they likely can relate closely to the fears of those who will inevitably turn into lobsters, dogs, or parrots.

Yorgos Lanthimos imagines this kind of dark and comical reality in his 2015 feature film, The Lobster. The film tells the story of David (Colin Farrell), a recently single man who journeys to an infamous hotel to forge a new relationship. David has 45 days to kindle this new bond, or he will be turned into a lobster (the animal of his personal choice). In the film, Lanthimos and screenwriter Efthimis Filippou reimagine the 21st century’s “hook-up culture,” with results and realities just as terrifying as the world the current generation faces.

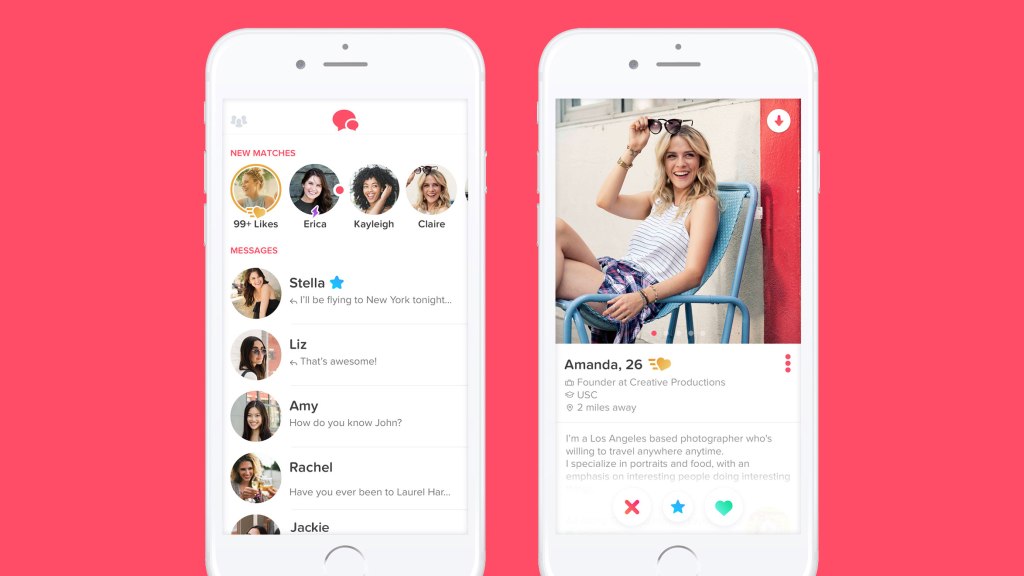

Hookup culture, as defined by Justin R. Garcia, refers to “uncommitted sexual encounters.” Apps such as Tinder and Bumble have become infamous for this kind of behavior, with Tinder specifically being known for its provocative nature. While users of these apps can expect a great deal more from their potential matches, such as a blossoming conjugal relationship, many use the service for one night stands and other limited encounters. Tinder, developed in 2012 by Sean Rad and Justin Manteen, was made to revolutionize the dating world, but in a very nontraditional sense. In an interview with TIME Magazine, Rad stated that he and co-founder Manteen “always saw the interface of Tinder as a game.” This addictive nature is certainly still felt by many in 2020, and the guests at the hotel in Lanthimos’s The Lobster felt this intensity as well, but in a different way.

In The Lobster, the hotel serves as the “Tinder interface,” where guests are driven by the concierges and workers to foster potential matches. The necessity of developing a relationship with someone in the hotel roots itself mostly from fear. Demonstrations, given by the hotel manager (Olivia Colman), ground the relationships out of fear and necessity. For instance, a woman shouldn’t walk alone, for she could be shot. When she walks with a man, she is guaranteed protection. These demonstrations, as well as the hotel’s sponsored dances and dinners, lead to lots of awkwardness amongst the guests. But the hotel isn’t responsible for fake behavior that correlates exactly with Tinder. Rather, the guests are responsible for it themselves.

About halfway through the film, David forces a relationship with a truly heartless and nefarious woman (Angeliki Papoulia). As could be expected, the relationship goes awry when the woman becomes aware of David’s falsified behavior. Many women and men can relate to the woman, as she was essentially “catfished,” or led to falsely contribute to a relationship. It turns out that many users seeking online love follow David’s path, with Internet guru Norton going so far as to estimate that one out of ten dating profiles online exists as a fake. And while David merely escape punishment, users who are catfished may not move on unscathed, with lost money, ambitions, and tragedy often at the other end of their path.

One of the most ironic elements of Lanthimos’s The Lobster results from how David ends up falling in love without force or oppression. He didn’t fall in love with any women present at the lifeless dances or bleak demonstrations; rather, he falls into love with the Shortsighted Woman (Rachel Weisz), one of the loners in the woods. The two revel in their rebelliousness to their respective factions, and as a result forge a real bond created out of love. Much like the hotel, apps such as Tinder lose sight of their end goal by their game-like nature. Why settle down when an even more attractive or successful match lies within one or two swipes? Lanthimos suggests that by putting down the phone or leaving preconceived notions about love and romanticism behind, a true relationship can form and blossom.

Yet apps aside from Tinder, such as Bumble, posit how relationships can develop outside of love or necessity for physical attraction. Over the last few years Bumble has added to its initial concept by allowing users to create matches for a new best friend or business purposes. These kinds of moves distinguish Bumble from its predecessor of Tinder, allowing users to implement the app to meet their needs. This only begs the question: what would similar hotels look like in The Lobster if they were set up for business purposes or friendships? Would the rules still be as strict, ideologies still so confined to their respective subject matter?

By thinking outside the box, Bumble has opened the floodgates even wider than Tinder did for online dating initially eight years ago. Similarly, Lanthimos has opened the satirical door wide open with regards to relationships in this technologically-advancing age. The incessant need for companionship can be completely lost when one’s nose finds itself buried in 5.5 inches of blue light day in and day out.